This blog post picks up my earlier exploration of Full Spectrum “Inclusive” Credentials. In this post, I’m going to explore how you can structure different types of badges for different recognition purposes and demonstrate the fitness of a badge for its purpose by including what I like to call a “badge content manifest”, otherwise known as a Critical Information Summary. Or more simply, a list of Requirements for the badge.

Before starting, I’ll say that this leverages some really interesting work I’ve been doing recently, helping develop a taxonomy and framework for the Inter-American Development Bank’s CredencialesBID initiative, who started badging in 2018 and have racked up a ton of experience in a relatively short time. I see them as innovators in the space. But also other clients before and since, both big and small. The result has been the development of generic “meta framework” that we provide to clients, along with badge content templates, whose scaffolded prompts match the requirements of the different badges in the taxonomy. This framework and taxonomy are flexible and adjustable (and evolving), but are also robust and coherent and most importantly, are based on experience and emergent practice, NOT pre-conceived policy. The more formal badge structures can be adapted for PLAR/RPL evaluation for credit, but the primary purpose is to clearly communicate the claims that badges are making and how those claims are supported – for ANY audience.

The taxonomy was developed for clients building badge systems on CanCred.ca and Open Badge Factory platforms, leveraging affordances like badge sharing, but the principles are actually pretty universal. I recently mapped a version of the framework for a UN agency currently using a competing platform.

Mapping a badge taxonomy

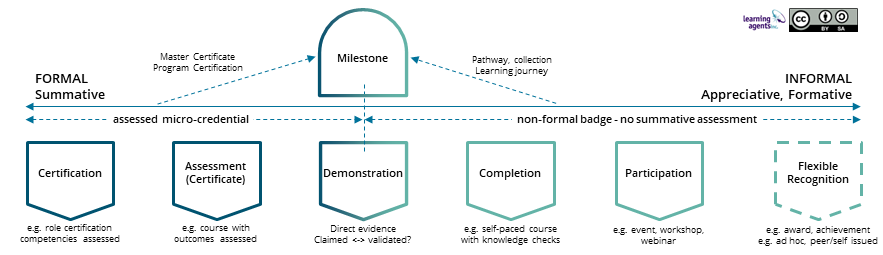

First, let’s review the top layer of the key diagram I shared 2 posts ago:

NB1: A Demonstration badge can be an evidence package or a live demo. It may manifest as an assessed micro-credential, or it may support self-claimed skills and achievements, or maybe a combination of the two, hence the dotted line, splitting it down the middle.

NB2: I made one revision from the previous version of this: digital badge has become “non-formal badge” because, in my opinion, micro-credentials are really just “formal badges”. I do understand the verbal shorthand of micro-credentials vs. digital badges up here in Canada, but I think it’s a bit binary and can lead to confusion,as this post may start to demonstrate.

Notice the examples provided underneath the different types of badges, such as “course with outcomes assessed” for the Assessment Certificate, a very popular type of micro-credential. Then there is the Completion badge, also very popular, but not really a micro-credential, if there’s no summative assessment. Unlike an Assessment badge, that you should be able to “fail” (otherwise it’s not really summative), you could probably bang away at the knowledge check questions in the Completion badge until you got them. If you evaluated specific examples of these different types of badges in the wild, you would expect to see some indication of the difference in the content of the badge, right? Well, not always, as the current leading candidate for the “Badge Hall of Shame” demonstrated in my last blog post.

Critical Information Summary: an evaluation tool

Enter the badge manifest, or “Critical Information Summary”, essentially a checklist of content elements that badge viewers should expect to see, so they can properly evaluate the badge. A “recipe for recognition”, if you will. The first I heard this term was in Oliver (2019), and the concept has since been adopted by frameworks such as Australia’s National Microcredentials Framework (“Critical information requirements and minimum standards”) and EU’s Recommendation on a European approach to micro-credentials for lifelong learning and employability (“European standard elements”). McGreal and Olcott (2022) have also developed a useful list, based on secondary research (Micro-credentials reference framework for university leaders). It’s worth mentioning eCampusOntario’s Micro-credential Principles and Framework (2020) as an early formative influence here in Canada, but it’s a bit more high level – somewhere between a framework and a checklist.

Problem is, these are all for micro-credentials. Can you say monoculture? What about less formal types of recognition, that might be just as useful and valuable, if not more so than an assessed course credential? The various webinars and MOOCs that didn’t require a summative assessment – useless? Not really. Even better, that employer testimonial, or that evidence package you assembled to support your self-claimed badge, or those endorsements you got from your co-workers? Or the Guru badge you were crowned with in your community of practice? Maybe that award you won in the hackfest at the makerspace? Or the heartfelt “Thank you” badge from the community association that actually tells the story of how you made a difference last summer? These are all different types of recognition, calling for different types of badges with different requirements to make them fit for their respective purposes. The authentic power of badged recognition often comes out of the specific context: the story that the badge can tell about you as an individual that other people might want to know and work with.

Building a content menu for a comprehensive taxonomy

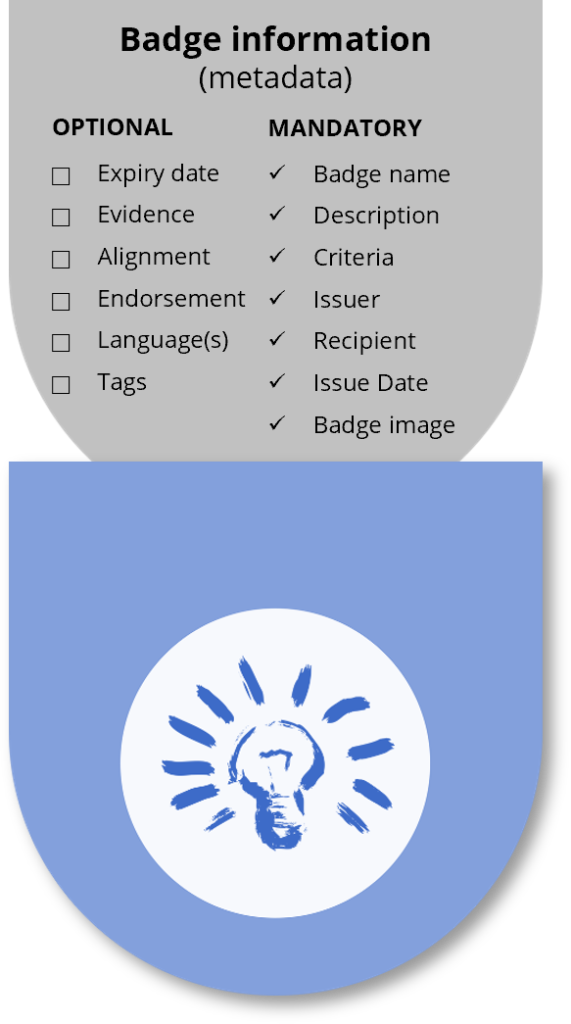

The Open Badge standard itself, with its mandatory and optional fields, makes a great starting point for differentiating badges. Fields such as Description, Evidence, Alignment and Endorsement can meaningfully describe what’s being recognized, if you take care in completing them.

But the most important field for many (including me) is Criteria, what I like to call the beating heart of the badge – what does it take to earn this badge? Problem is, Criteria is a blank canvas, because Open Badges are flexible. Blessing and curse – it has led to some pretty poorly written criteria (did I mention the Badge Hall of Shame?)

Guidance for Criteria

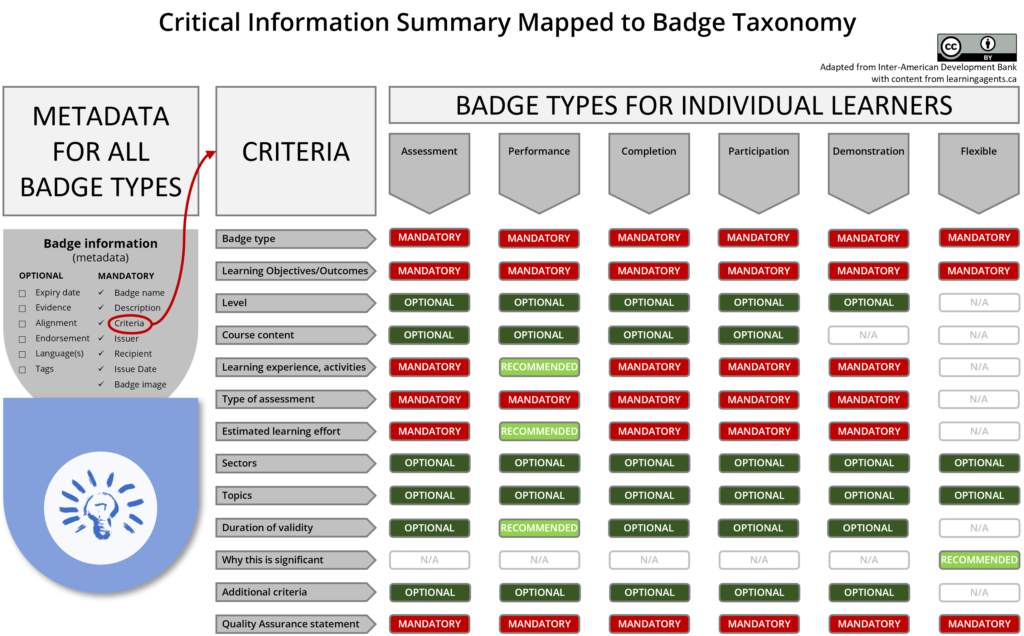

To help manage quality AND fitness for purpose, we have developed custom Criteria content models for the different types of badges. Here is a generic version of a Critical Information Summary menu that I helped develop for the Inter-American Development Bank’s CredencialesBID initiative. The Criteria field breaks out into a series of options, recommendations and mandatory requirements:

(NB: I removed some really interesting community of practice badges to reduce complexity, but I also included a Demonstration badge, the newest element in my evolving taxonomy, not part of the CredencialesBID taxonomy.)

The Open Badge fields and the Critical Information Summary menu for Criteria form the basis of the content templates for each badge, each with its own text scaffolding. These templates can be packaged as text Requirements documents for offline preparation or as badge “blanks” that can be copied into client badge environments to guide creation and can be further adapted to fit local needs.

Since they introduced their badge Requirements documents, CredencialesBID has reported a significant reduction in costly revisions and a much smoother badge production process from the enhanced clarity. So it’s worth doing!

In later posts, I’ll provide a bit more detail about the text scaffolding and I’ll also revisit the design of badge images – not just as branding opportunities, but as signposts for the meaning of your badges – making learning, skills and achievements more visible.