Or are they just competent?

ANSWER: probably not qualified as teachers, but possibly competent to teach, i.e. to do more than provide knowledge dumps from their domains of expertise, depending on their attitudes toward teaching and their experiences with professional education and lifewide learning.

Apologies for the clickbait title, but I hope to use this post to make some points about qualifications, knowledge, competency and performance, with a few swipes at micro-credentials as the self-elected gold standard for competency.

Yes, post-secondary faculty can be relied on to have a Masters degree or better, but that’s typically in their subject domain, right? Not many have degrees in education, although some do. If they do, I’d argue that those degrees aren’t typically designed as professional preparation, like you see for student teachers at the K12 level.

And in terms of advancing academic careers, we do often hear that research achievements are valued more than demonstrated teaching skills, don’t we?

In the Canadian college system there IS more attention paid to pedagogy (many colleges even use the word “andragogy”), partly because colleges often recruit from industry and must quickly bring them up to speed. I still have my RRC Poly Train the Trainer binder from 2000 for example, where I first learned about the DACUM process. But my learning outcomes were not “rigorously assessed”, so who knows what damage I did…

Most students across PSE are still taught by faculty who are not officially qualified to, well… teach. Compare this to K12, where the provincial College of Teachers has very specific requirements for certification, including workplace performance.

So why do we respect post-secondary education? You do hear stories about fossilized professors, overflowing lecture halls and obsolete curriculum, but by and large (at least here in Canada), most PSE does not suck. Why is that?

I’m suggesting three reasons here, and I’d be happy to hear other people’s ideas on them:

- Professional practices : within departments and faculties and in the broader professional community with colleagues across institutions (i.e. self respect, mentoring, and support from superiors and peers)

- Institutional practices: internal QA, professional programs, direct ID support for faculty from internal T&L centres, encouraging excellence generally and protecting the brand, locally and virtually)

- External accreditation: the big stick – you don’t want to lose your accreditation, especially as a professional “school”.

(But bear in mind that an accreditation process can be little more than a multi-annual bureaucratic “tick box” chore, with your more embarrassing fossils and departmental processes safely locked away from view. And rest assured, few in industry actually comprehend what your accreditation really means. They’re more concerned about high level perceptions of your brand and personal experience with your graduates.)

So, how do post-secondary faculty learn how to teach, and to teach better? Here’s another list:

- White collar apprenticeship: Coming up through the ranks as students, Teaching Assistants, etc. This can include mentoring, but also flying by the seat of your pants (social learning, experiential learning…)

- Induction and onboarding training courses, such as my Train the Trainer course at Red River Poly (nonformal learning)

- Professional education, perhaps offered out of the institution’s Teaching and Learning Centre, or from third parties such as eCampusOntario (also nonformal learning)

- Community of practice: interacting with colleagues inside and outside the institution, online and IRL

- Personal learning: Experience, reflection, reading, writing, etc.

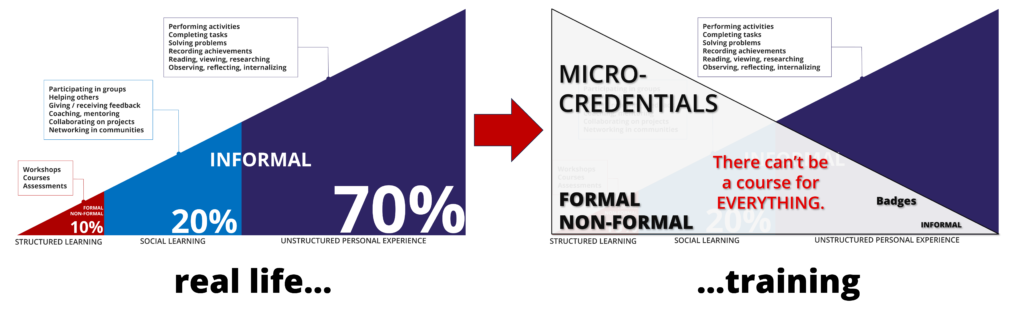

So, no credits, no qualifications. Some of this learning is structured, maybe including micro-credential courses and program certificates (like eCampusOntario’s Ontario Extend), but that’s pretty recent… a lot of the learning is just social and experiential. Lifewide. In the wild. Hanging out. In the flow of work.

Isn’t it ironic, amid all the pious talk about skills and the need for rigour and quality assurance in skills development systems and micro-credential programs, that we have so few rigorous programs in place to ensure the skills of post-secondary educators, who are developing so many of those micro-credentials? Is academic freedom that powerful, that all we can have is encouragement for the “scholarship of teaching and learning” and “centres of excellence” and professional education, avoiding the word “development”, as being too directive?

Let me be clear: I’m not saying there should be mandatory professional development programs for PSE educators. What I am saying is what my mother used to say: “What’s sauce for the goose should be sauce for the gander.” What works for engaged PSE educators should be applicable to others.

Why can’t we come up with better ways to recognize learning where it happens… for PSE faculty and everybody else? Why is a training course the first and often ONLY thing that educators can think of when it comes to skills development?

Cue a stop-motion version of my 70:20:10 video homage to Monty Python (click to expand):

And why is the focus always on individual skills, instead of team performance or organisational effectiveness? What if you do actually learn that new skill but you’re blocked from applying in back in the workplace due to obsolete business processes and a crappy workplace culture? Organisations have to learn and change too, not just individuals.

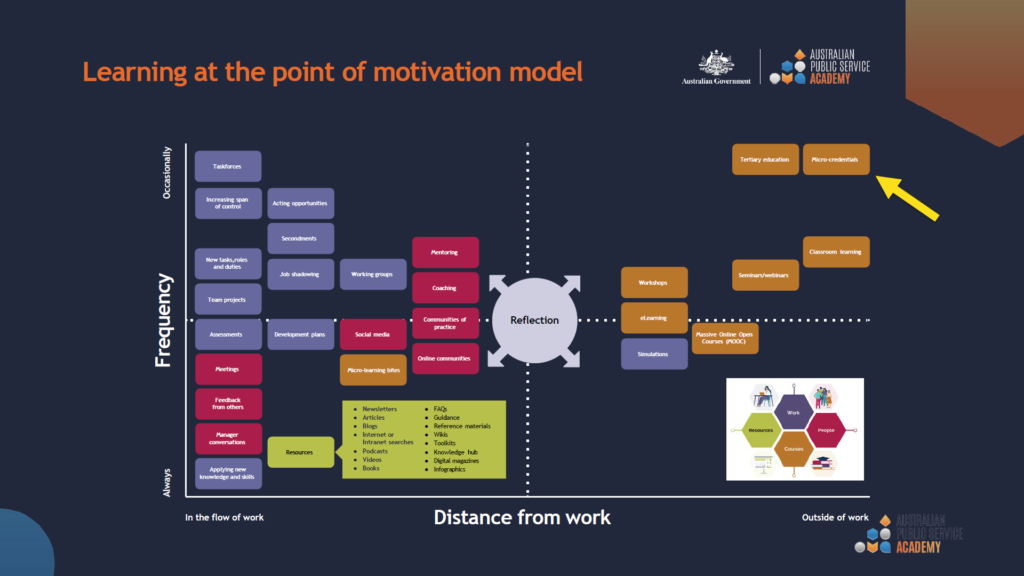

I love this matrix below that 70:20:10 guru Charles Jennings recently pointed me to. He helped develop advise on it for the Australian Public Service Academy. It’s based on research that shows that learning is most effective when closest to its application: “learning in the flow of work”(*) is the ideal, and so are multiple opportunities to apply that new learning in your context in order to change your ongoing behaviours. That’s why this graphic maps learning experiences in terms of frequency and distance from work.

(*SIDENOTE: Beverley Oliver called this “Learning Integrated Work” when I interviewed her about the 2021 UNESCO report on micro-credentials, deep-linked here. So it is possible to contemplate this stuff from inside PSE. I miss her voice in this community.)

Charles would shift a few things in what they produced here, and so would I, but do you see where they’ve put micro-credentials? (arrow is mine). Looks like Pluto way out there…

(click to expand the graphic – makes Pluto seem a little bigger…)

Heh, poor Pluto. I might not have been quite so cruel; I am Canadian, and we’re usually more subtle with our cruelty. There ARE some great examples of authentically applied learning in micro-credentials, but not THAT many. (See that? A open face Canadian feedback sandwich.)

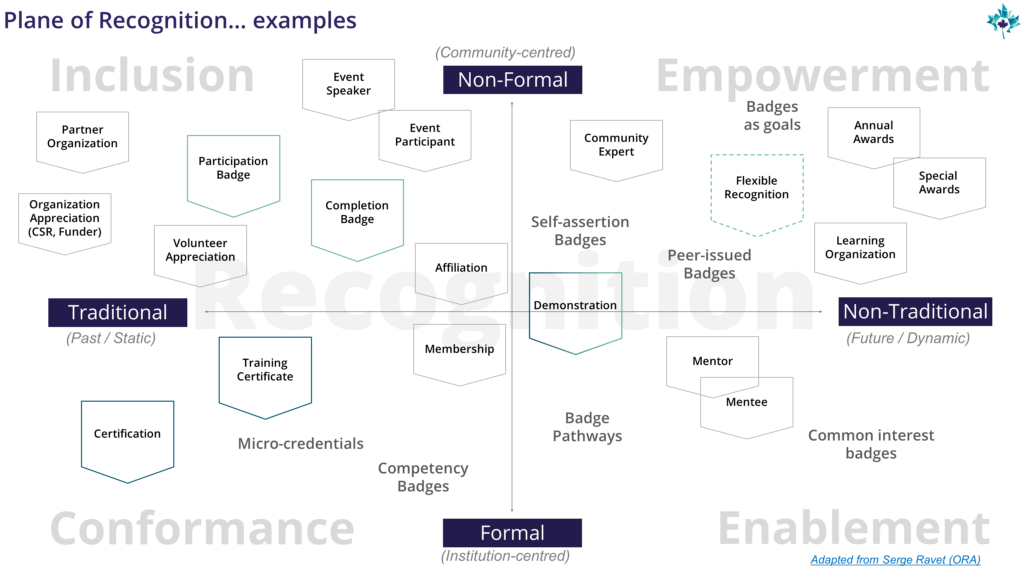

I’m becoming more and more excited about the convergence of 70:20:10 learning and performance with open recognition, similar to how Serge Ravet is currently cross-mapping Wenger’s community of practice concepts with open recognition – you can actually see Communities of Practice explicitly displayed above. So we’re really discussing different aspects of the same elephant in the room. I connected with Charles Jennings this week after the 2023 Institute for Performance and Learning(*) conference in Toronto, and I’m now working my way through the 2016 book he co-authored with Jos Arets and Vivian Hiejnen, entitled “702010: towards 100% performance”. Here’s a quick framing quote:

… (70:20:10) enables L&D professionals to connect more quickly and effectively to what really matters: learning and performance at the speed of business. It isn’t just about providing formal learning solutions. With 70:20:10 as a reference model, more and more L&D professionals are co-creating with the business. This movement makes L&D more relevant to organisations.

702010: towards 100% performance

(*SIDENOTE: It’s interesting to me that I encountered Charles and 70:20:10 at a conference for Canada’s workplace L&D professionals, which DOES have a certification program but which also recognizes the shortcomings of formal training and education, as exemplified in their 2015 rebranding from the Canadian Society for Training and Development to the Institute for Performance and Learning, to better foster solutions “that engage, enable and inspire adults to perform at their best and make the organizations where they work more successful, innovative and productive.”)

For my part, I want to help counter what Dominic Orr called out on LinkedIn after the recent ICDE Global conference in Costa Rica:

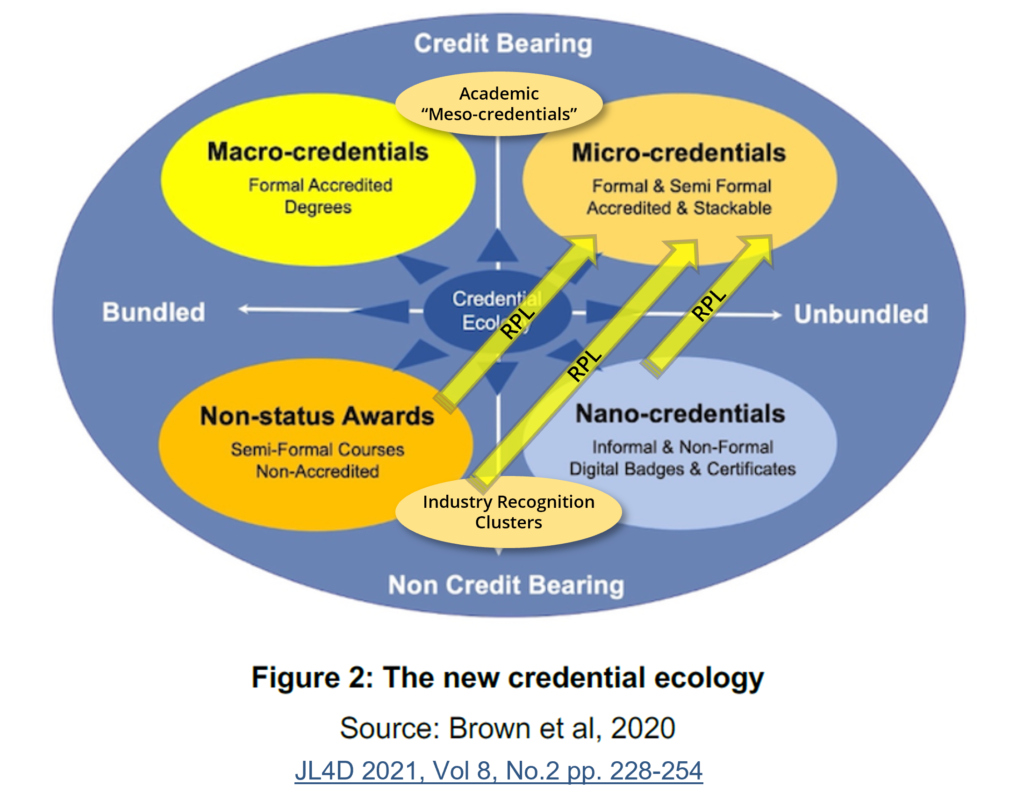

We notice that many are beginning to use the term microcredentials as an abbreviation for short learning programmes, and see this as a stark reduction of the original aims of using new forms of credentialisation to open up and innovate in the learning space.

Dominic Orr

(LinkedIN – bolding mine)

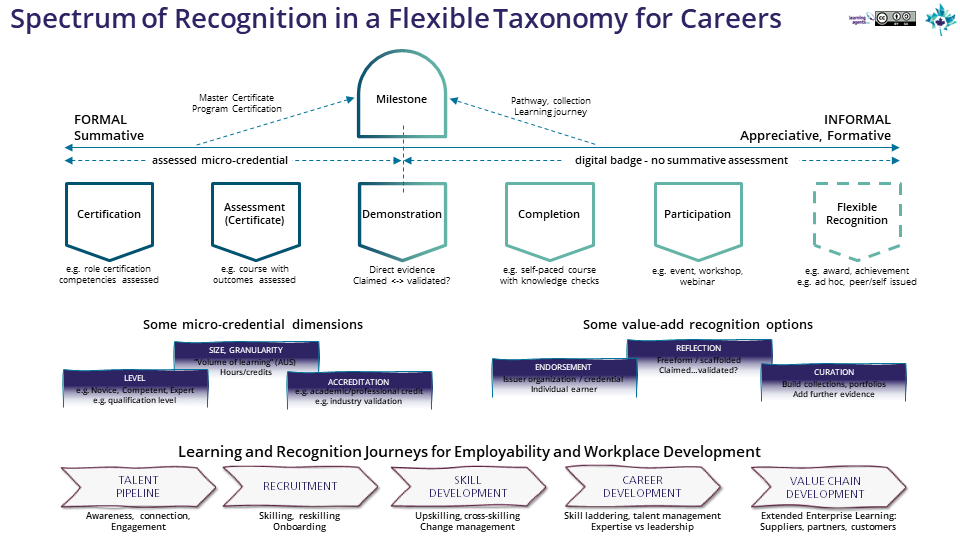

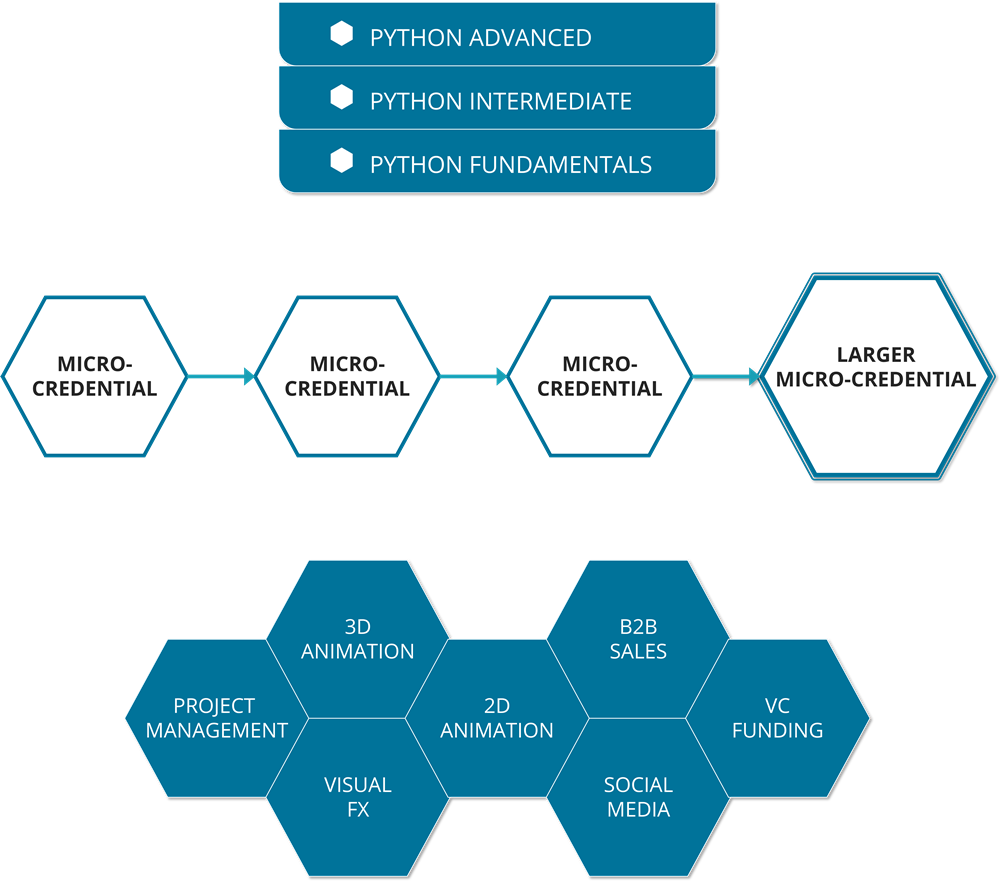

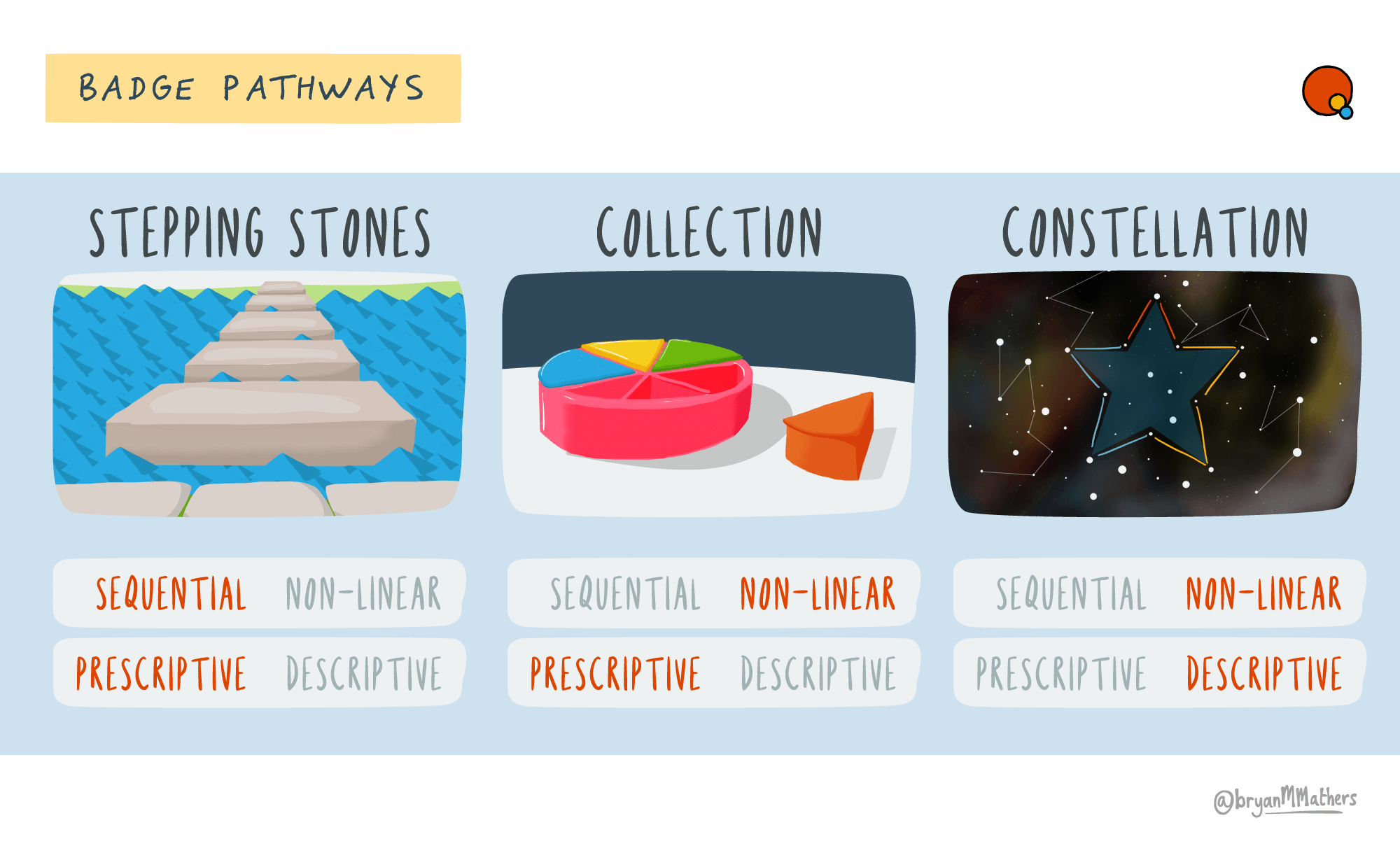

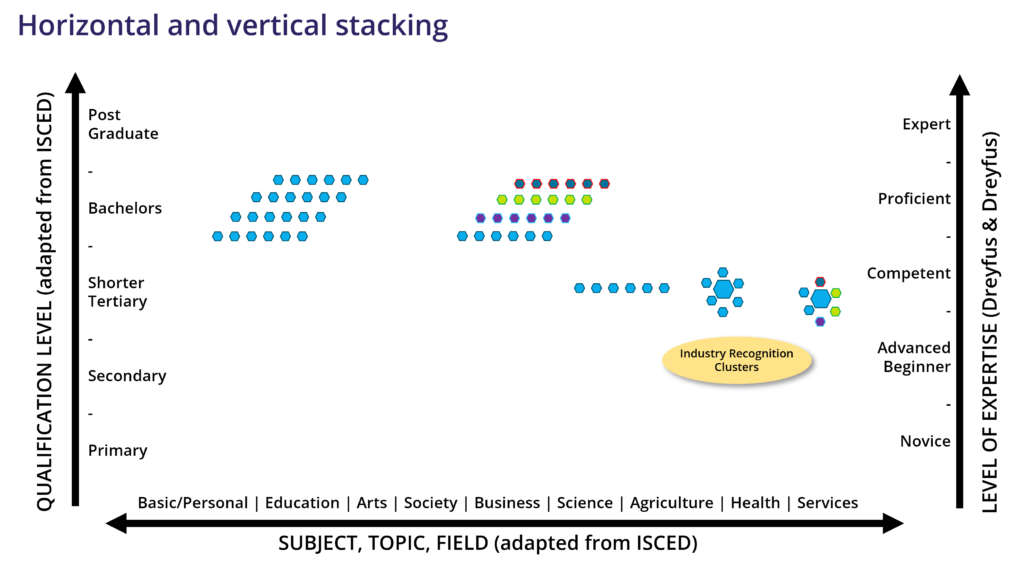

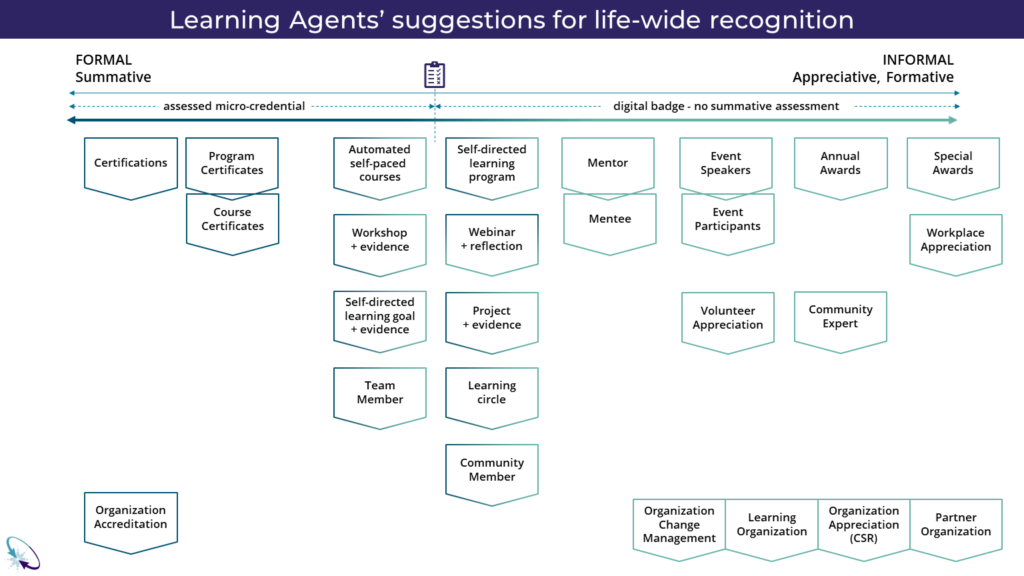

Recently, I’ve been sharing a “populated” version of the inclusive spectrum of recognition, I earlier shared at CAUCE, as below, with badge ideas to get people’s creative juices flowing:

I’ve also tried mapping some of these to Serge’s Plane of Recognition in the current version of CanCred’s Badge Canvas:

And I want to share an awesome badge on assessment that I earned from some exemplary educators connected with the Commonwealth of Learning:

I wouldn’t call this a micro-credential badge, although my badge application was lightly assessed. More important, it’s a learning capsule, containing the content and my reflections on the content, which I can refer back to, at any time. And I have, particularly the session with James Skidmore, for its wide-ranging scope and really useful references. Portable learning, that I can use at time of need.

In the near future, I hope to collaborate with Charles and Serge Ravet on a discussion paper to encourage educators, L&D professionals AND LEARNERS to get beyond knee jerk responses to skills development and to stop leaving so much valuable recognition of skills and performance on the lifewide learning table.

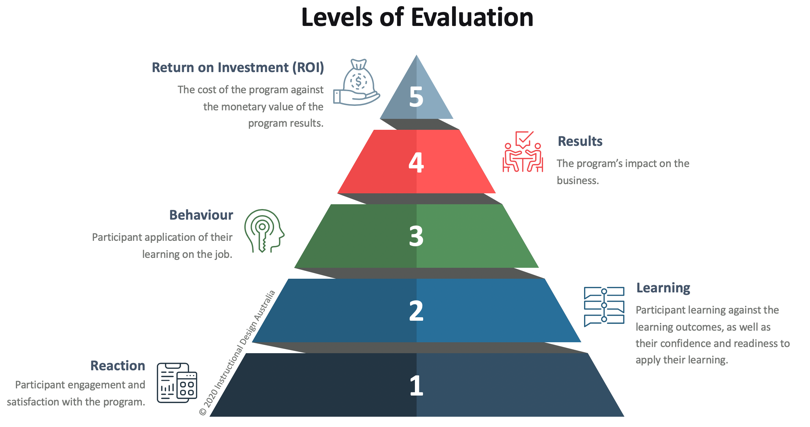

Yes, it’s easier for funders and educators to generate automated courses on electric cars and AI ethics and then count the number of beans completions as an output. But it’s not very agile and ultimately doesn’t speak to levels 3, 4 and 5 in the Kirkpatrick/Phillips model below, does it?

Doesn’t it make more sense to encourage and track learning at what Charles Jennings calls the “coal face”? Messier, yes. Harder to assess and track, yes. But that’s where the value gets mined.

In future posts, I hope to talk more about sustainable ways to mine that value.